By Nico Mesterharm

The Berlin Wall may have fallen in 1989, but nostalgia for communist East -Germany lives on in the hearts of approximately 4000 Cambodians who took refuge in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) during the civil war of the 1980s. On my first documentary shoot in Phnom Penh in the year 2000, I had interviewed a few of them. To them, the GDR was paradise. They were saying made slightly sarcastic remarks like: “funny” things, such as: “In East Germany you had to queue for toilet paper, but at least they had toilet paper.”

When I founded the Cambodian-German Cultural Center “Meta House Phnom Penh” in 2007, I decided to find out more about the experiences of Cambodians in the GDR. Being born in the Federal Republic (West -Germany) and raised in close proximity toof the Wall in West -Berlin, I wanted to understand why Cambodians had fond memories of what looked for many of my compatriots like a (failed) communist dictatorship.

We were the children of the “Cold War”, which was fought on strange battlefields. For example, the “Hallstein Doctrine” (1955-1970) – named after West -German state secretary Walter Hallstein – prescribed that Federal Germany would not establish or maintain diplomatic relations with any state that recognized the GDR. Since the middle of the 1950s there have been official contacts between the Federal Republic and Cambodia, which led to the first agreements on economic cooperation in 1960 and 1962. The establishment of the West -German -representation in Phnom Penh (1964) was followed by the establishment of full diplomatic relations at an ambassadorial level on November 15, 1967.

However, those relations ended when the late King Father Norodom Sihanouk – then the Cambodian head-of-state – formally acknowledged the GDR as a sovereign state on May 8, 1969. Ironically, the Doctrine was also not ever applied to Cambodia;. Sihanouk became so angry about negative West -German press reports about his close relations to the GDR that he officially expelled West -German diplomats before the German state could take action.

From 1969-1975, the GDR was sending experts and teachers to Cambodia, while a few Khmer students were admitted to East -German universities. When Pol Pot took power, the Khmer Rouge broke off diplomatic relations with the Warsaw Pact nations, because of its closeness to China and Beijing’s “Anti-Comintern”-line. After the Khmer Rouge had already begun their war with Vietnam, GDR politburo chairman Erich Honecker sent New Year’s wishes to Khmer Rouge head of state Khieu Samphan on Dec 29, 1977, via the Cambodian Embassy in Hanoi. Forty-eight48 hours later, Cambodia sent Honecker a message via the GDR Embassy in Beijing announcing that Cambodia had severed relations with GDR’s close ally Vietnam, a message Honecker refused to accept.

When the Vietnamese “liberated” Cambodia in 1979, GDR diplomats returned to Phnom Penh and established relations with the “People’s Republic of Kampuchea” (PRK). The state treaty for the education of Cambodians in the GDR, reached in the same year, was the first after the end of the Pol Pot era. Following the genocide Cambodia lacked the skilled labor needed for the rebuilding of the nation. Up until the collapse of the GDR and the eventual reunification of Germany in 1990, young Cambodians studied and gained skills in East Germany. After finishing their studies and training they had to return to Cambodia and put their skills into practice. In addition to this, the GDR supported Cambodia with a variety of aid projects.

Contrary to this, “my” West -German government – under the leadership of Helmut Schmidt and (later) Helmut Kohl – was following its American allies, who sided with China and ASEAN against Vietnam and the Soviet Union. This was obviously to punish the Vietnamese communists for their victory in the Vietnam War, which had only ended in 1975. The result of this diplomatic charade in 1979 was to prolong the life of Pol Pot’s Democratic Kampuchea by handing it the Cambodian seat at the UN. With U.S. backing, Cambodia would continue to be represented in the United Nations by a Khmer Rouge diplomat until 1993.

International aid poured into the coffers of the Khmer Rouge, abetting their war to retake power. West -German taxpayers funded roads for the Khmer Rouge at the Thai-Cambodian border; the West -German arms manufacturer Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm (MBB) sold a lightweight unguided anti-tank weapon (“Armbrust”) to the Khmer Rouge jungle guerillas, who fought the Cambodian government with it. A number of ultra-left West -German activists – who became very influential in re-unified Germany – collected money for the Khmer Rouge movement in 1981, when it was already clear that Pol Pot’s regime was responsible for the death of 1.7 million Cambodians. This is even more unsettling if you take into account that Germany had it’s own genocide under Hitler, which should have prevented the West from even considering any kind of assistance. Moreover, “we” have never apologized for this.

This was discussed during the opening panel for the exhibition “The Legacy of the Khmer Rouge” at the Berlin “Academy of the Arts”, which I had been co-curating. While conducting this project it became clear that most of the details had are already been forgotten. Important time witnesses are very old or have passed away. The end of the cold war and the German reunification preceded the UNTAC (United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia) mission (1992 to 1993). A year earlier, the international community had met in Paris to establish a plan to intervene and establish peace in Cambodia, which produced the Paris Peace Agreement. The Paris Peace Agreement established UNTAC’s mandate to oversee free and fair elections, promote the respect for human rights, resettle refugees, disarm and demobilize the factions involved in the civil war, establish the rule of law, and reconstruct infrastructure.

With more than 20,000 “blue helmets, the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) became the biggest peace mission in the UN´s history. Through the restoration of the democratic order and the implementation of free elections, the civil war in Cambodia ceased. Under the UN mandate the German army (“Bundeswehr“) supported the UNTAC mission by operating a hospital in Phnom Penh, which Cambodians named “House of Angels”. After the implementation of free elections (1993) a German embassy opened in Phnom Penh again. The reunited Federal Republic of Germany had established diplomatic relations with Cambodia

In the course of the first 11 years of “Meta House,” we have also produced a number of photo exhibitions and video documentaries about Cambodians in the GDR, in cooperation with the Goethe-Institute and the Rosa-Luxemburg-Foundation. However, we did not manage to find funding and / or broadcasting partners in Germany to investigate the completely different German/German approaches to the “Cambodian disaster”, as the decision makers of reunified Germany have been decided against publicly highlighting the achievements of GDR foreign policies and aid, also in regards to Africa and Latin America. It seems to be more consoling to focus on the political repression, the limitations of human rights and the weak economy of Honecker’s state in order to proveof to younger generations that “the West was always better”. Those Cambodians, who participated in the GDR’s educational program and the Germans they met and became friends with can tell you a different story…

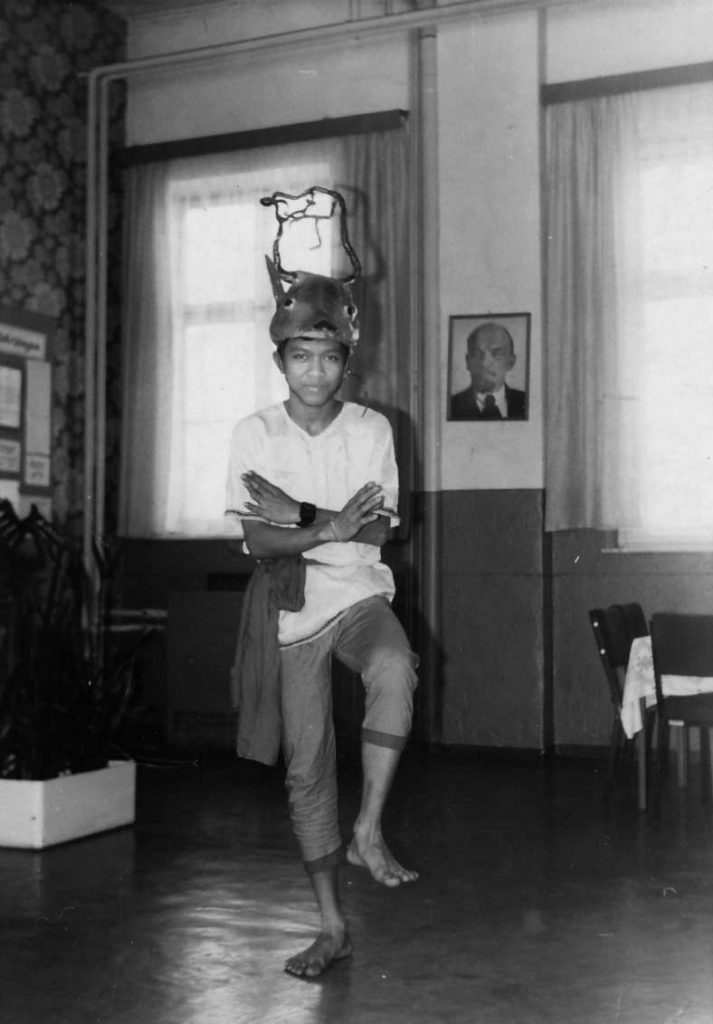

The two photos that are included in this publication are part of our Meta House archive in the framework of the multi-media -project “Far Away from Angkor”. The magazine cover photo has been contributed by Walter Rudeck, the former GDR’s state secretary for vocational training. Rudeck, who was responsible for similar programs throughout Asia (North Korea, Laos, Vietnam), said that the Cambodians took best to life in Germany. The black-and-white photo was provided by one of our current Meta House German-language teachers, Kaoeun Kannika, who went to the GDR at the age of 16 to study car mechanics.

Nico Mesterharm (born 1967) is a German journalist and filmmaker. After having shot many documentaries about Cambodia in the early 2000s, he decided to settle in Phnom Penh and to found the country’s first independent arts & media center “Meta House Phnom Penh”, which has officially representeds the German cultural foundation “Goethe Institute” since 2015.