ARTS AND MEDIA FOR RECONCILITATION

ARTS AND MEDIA FOR RECONCILITATION

The ultra-communist Khmer Rouge regime ruled Cambodia from 1975 to 1979. At least 1.7 million people are believed to have died from starvation, torture, execution and forced labor during this period. The end of Pol Pot’s rule was followed by civil war, which finally ended on December 29, 1998. In 1997, the Cambodian government requested the United Nations to assist in establishing a trial to prosecute senior leaders of the Khmer Rouge. The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) were established by an agreement between the Government of Cambodia and the United Nations in 2004. The first case began in February, 2009.

Since then, the ECCC has been a critical driver of debate and the country’s reconciliation with its past. The tribunal has compelled parents to discuss the history of the country with their children, and it has compelled young people to ask more critical questions about the role of government, human rights and authority. Three recent Meta House projects under the ECCC umbrella are dedicated to Cambodia’s young generation and the legacy of the ugly Pol Pot years. These projects – implemented by Meta House with other NGO partners receive support by multiple donors.

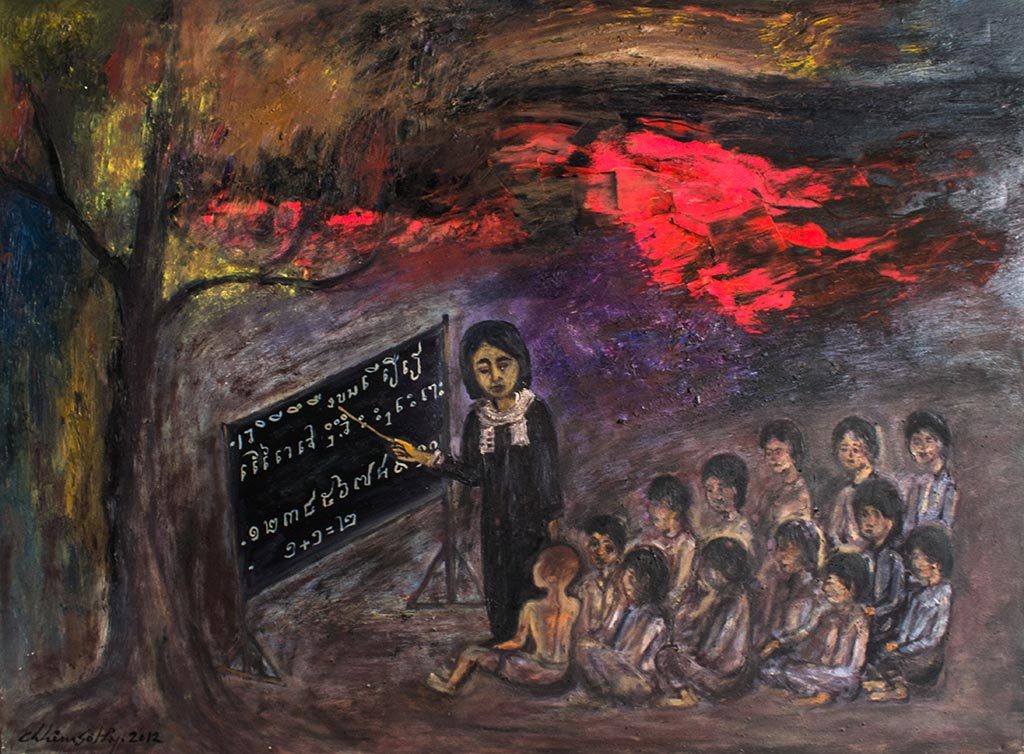

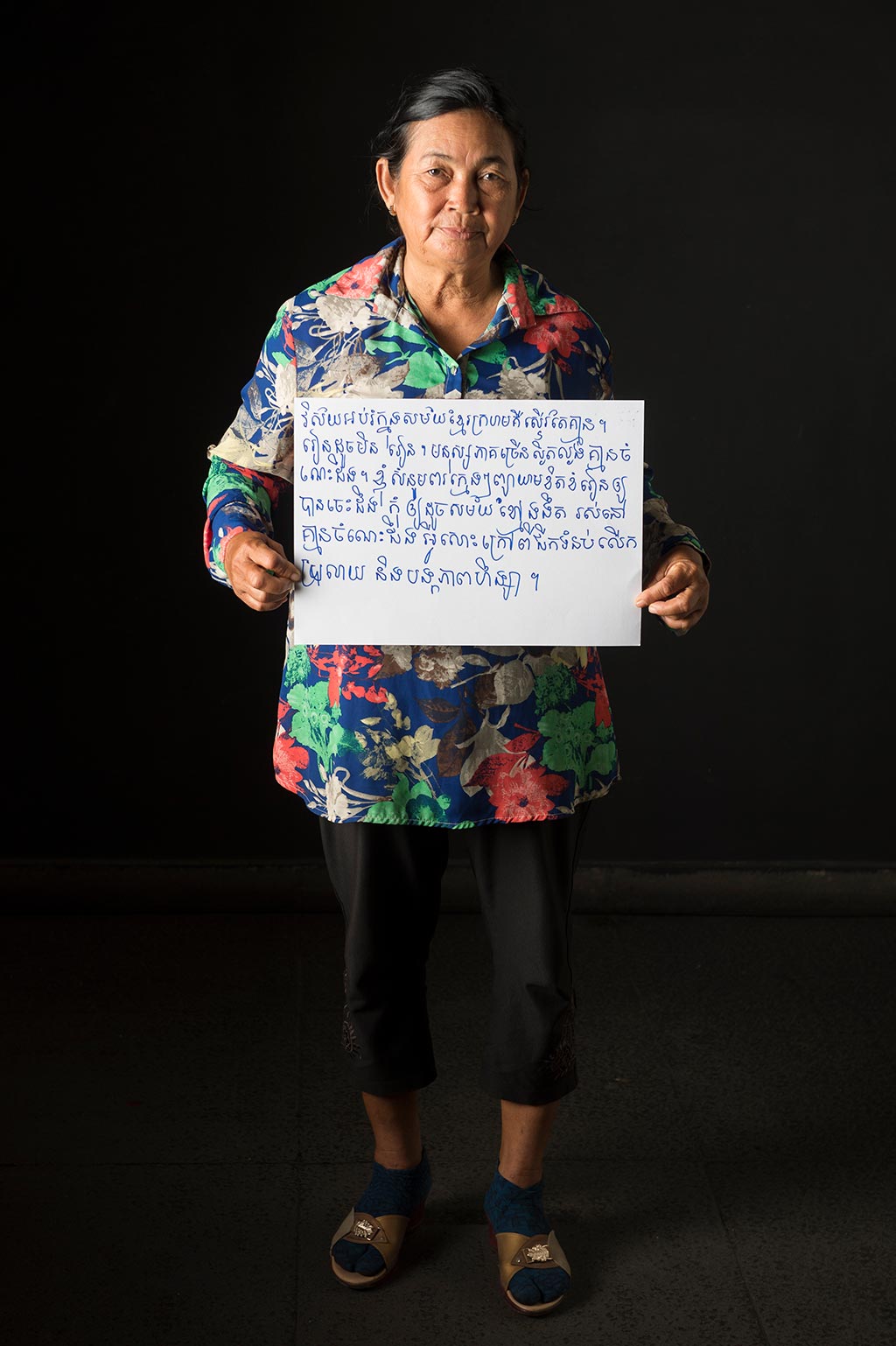

All projects thrive through direct participation of Khmer Rouge survivors (so-called „Civil Parties“), who share their experiences with high-school and university students nationwide. The additional photo project „Lessons from the Past“ documents which experiences older Cambodians want to share with the youth. Photos are exhibited on school yards together with a series of paintings by Cambodian artist Chhim Sothy, who reflects on his childhood in Pol Pot times.

The educational system was the first one to be disintegrated by Pol Pot’s government. Schools nationwide were ordered to be closed. Teachers were among the first victims of the Khmer Rouge’s purging as they radically were preparing a massive indoctrination program for the youth. In fact, 90% of the teachers that time were killed while the rest fled the country or stayed in anonymity.

The educational policy of the Khmer Rouge was very strong on “technical skills” – namely the skills required to grow rice, to fish, to farm, as well as to share simple medical knowledge. The goals were not about personal advancement but, rather, the advancement of the collective. The new “school system” was designed to “teach” not through classroom activities but through physical labour.

The painting was created by artist Chhim Sothy, who remembers the following: “Every day after lunch, I and other children received a one-hour-lesson to study reading. In fact, I did not want to study because the lesson was the same over and over again. I already learned something before Khmer Rouge, so I just went in, read a few words, and got out to look for crabs, snails, and other things to eat. The teacher was another Unit chief. And the lesson was about the revolutionary development. I remembered a sentence: “Democratic Cambodia is rich, we have rice fields and levee everywhere and the people try to do the agriculture to improve their life.” It took almost two months to finish the sentence. If you were able to read 2 or 3 words you would be allowed to go out and looked for something to eat.”

Phat Toch, 60 years old, was born in Krong Pkar village, Soportep commune, Chbarmon district, Kampong Speu province. During Khmer Rouge, she was forced to join the lesson under the tree every afternoon after work. There was no real education. Most of the children agreed to participate the class because they got scared of being killed. This is what she wants the young generation to know: “The education in Khmer Rouge period was emptiness. That was the lesson that could not educate you to learn anything. Almost everyone could not read. I suggest to the next Cambodian generations, please put more passion in learning and get way from any actions that could create the dark era like that regime which people were blinded by anger, knew nothing besides digging canals, and committing violence.” (Photo by Anders Jiras)

REPERATION PROJECTS

REPARATIONS PROJECTS

* The Turtle Club/Courageous Turtle project promotes peace, memoralization and reconciliation through community theatre and intergenerational dialogues. Part of this is the Civil Party photo project Lessons from the Past. This project has received funding from the European Commission, the German Institute for Foreign Relations through the German Foreign Office, Smart Telecom and Freshy.

* The Cham People and the Khmer Rouge empowers young Cambodian Muslims to produce films about the recent history of their ethnic group, which are to be screened and discussed in respective communities. The Muslim Chams numbered at least 250,000 in 1975. With their distinct language and culture, large villages, and independent national organizational networks, the Chams could have threatened the atomized, closely supervised society that the Pol Pot leadership planned to create. This might have been one reason why the Cham were specifically targeted by the Khmer Rouge. The project has received funding from the Swiss Embassy in Bangkok and the German Heinrich-Boell-Foundation.

ART OF SURVIVAL

ART OF SURVIVAL

The first intergenerational Khmer Rouge Art Project

Democratic Kampuchea was one of the worst human tragedies of the 20th century. Nearly two million Cambodians died from diseases due to a lack of medicines and medical services, starvation, execution, or exhaustion from overwork. Tens of thousands were made widows and orphans, and those who lived through the regime were severely traumatized by their experiences. Several hundred thousand Cambodians fled their country and became refugees. Millions of mines were laid by the Khmer Rouge and government forces, which have led to thousands of deaths and disabilities since the 1980s.

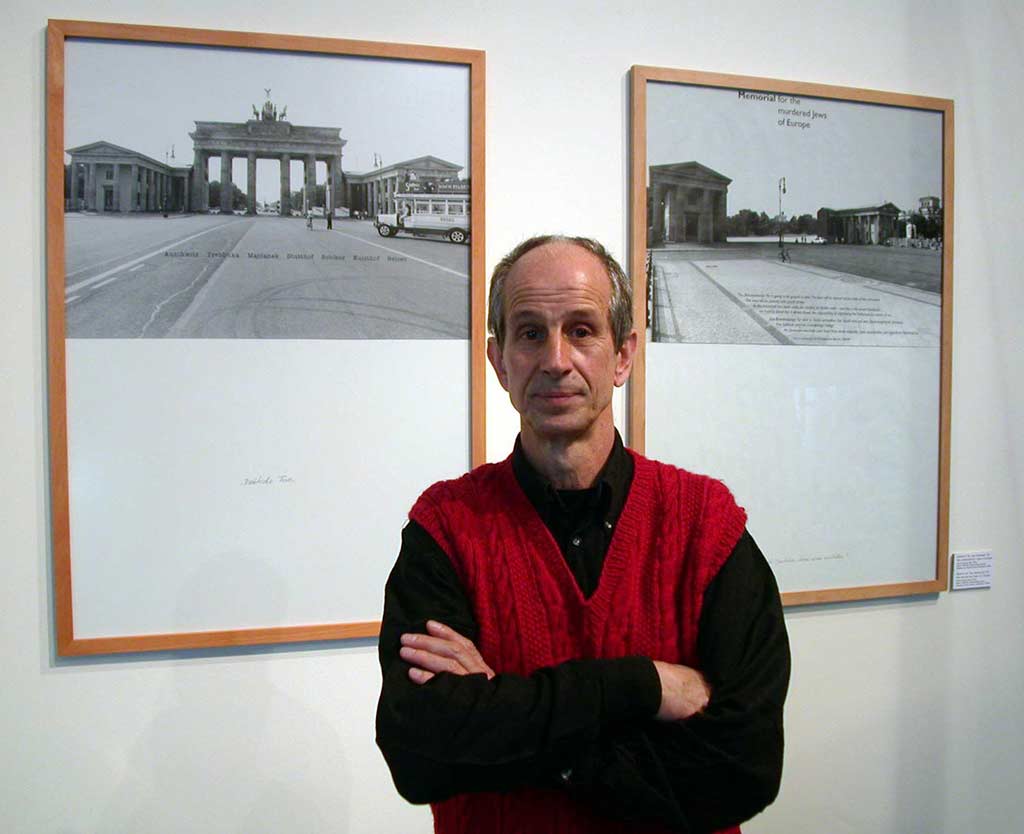

The Cold War killed any prospect of a tribunal. Justice was all but frozen for decades –until 2006. In that year, the UN-backed Khmer Rouge Tribunal (ECCC) was finally established in Phnom Penh. Coinciding with the trial, our project Art of Survival (AOS) began in January 2008 with 21 artists and expanded in October 2008 to include a total of 40 artists, who were each given a blank canvas to document their reflections on the Khmer Rouge period. Among them were a few international artists such as Vietnamese-Khmer painter Le Huy Hoang, Americans Rodney Dickson and Bradford Edwards, Francis Wittenberger (Israel) or Herbert Mueller (Germany).

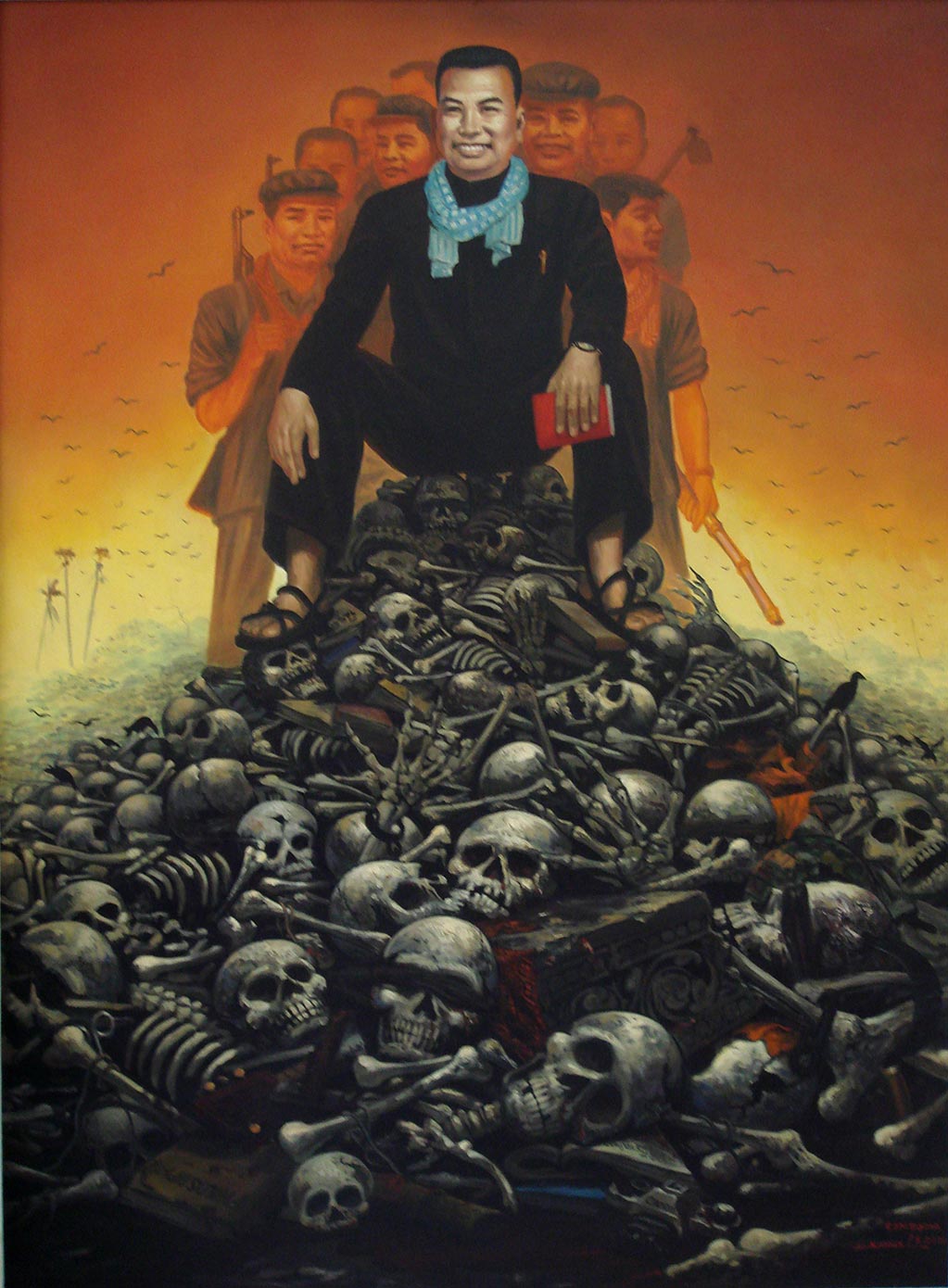

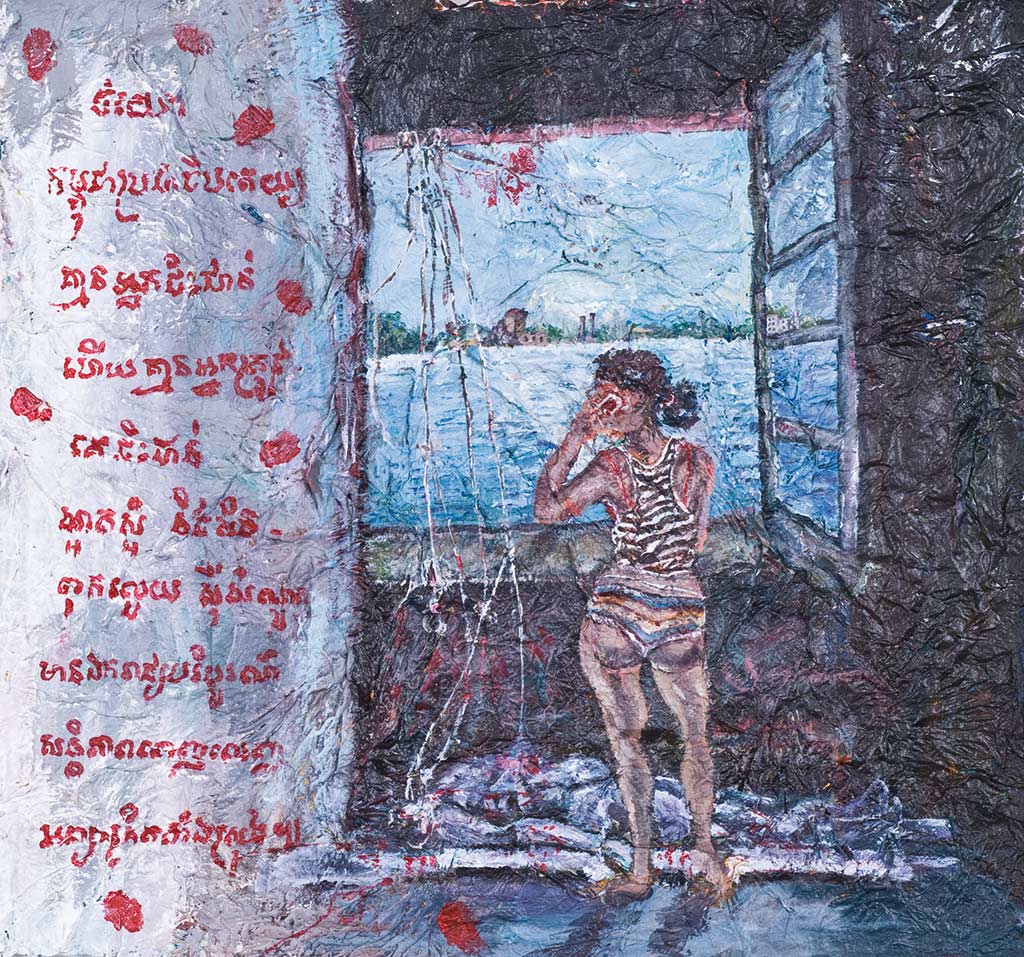

Cambodian female artist Oeur Sokuntevy was born after the atrocities of Pol Pot’s regime in 1983. So when she was asked to produce an artwork for an exhibition looking back at that period, she struggled; Pol Pot and the legacy of his rule are not discussed much by her generation. In the end, Oeur painted “I Am Too Young to Understand These Words,” a watercolor of a young girl in a bathing suit talking on her mobile phone beside a phrase reproduced from Pol Pot’s “Little Red Book,” extolling the regime’s aims. Her painting stood in sharp contrast to “The Khmer Rouge Leader,” a painting by Hen Sophal, born 1958, who depicts a grinning Pol Pot seated like an emperor atop a mountain of bones and skulls. In this regard, AOS was a “long-overdue dialogue through art”. Works artists from different generations were representing the divergent perspectives of Cambodians on Pol Pot and his killing fields.

The highly popular AOS exhibitions at Meta House and Bophana Center were accompanied by the intercultural dialogue project “Underground” (with German artists Horst Hoheisel and Sebastian Brand, funded by the Goethe Institute), and a series of speaker events at Pannasastra High School in Phnom Penh. In 2009, the Art of Survival traveling exhibition, funded by DED (German Development Services) took a selection of artworks to Cambodian villages. “To us it makes perfect sense to approach these darkest years in Cambodian history through visual arts as the Khmer Rouge forbade everything which was related to creativity and freedom in music, visual, and performing arts”, said German co-curator Lydia Parusol in an interview with the US “Newsweek” magazine. “Cambodia’s artists, who influenced the Southeast Asian subcontinent in the 60s, died or fled into exile. In recent years, Cambodia’s art scene has blossomed again and Meta House is a part of that.”

Funding

Partners